|

Born in Berkeley, Calif., on Oct. 2, 1921, he took his first flight at age six in a Union Oil Company airplane piloted by Carl Lienesch, a friend of his father. Although Lienesch later claimed young Crossfield, seated in the front cockpit of the wire-and-fabric biplane, fell sound asleep after about 45 minutes the boy was hooked on aviation for life.

At age 12 while working as a delivery boy for the Long Beach Press-Telegram, Crossfield started taking flying lessons at a small airport in Wilmington, Calif., trading newspaper delivery, sweeping out hangars and washing airplanes for flight time. He became a self-described "airport bum" and gradually acquired many hours of flying experience.

Crossfield not only wanted to fly airplanes; he also wanted to learn how they worked. As a boy, he designed and built radio-controlled flying models. He began his formal engineering training at the University of Washington in 1940. Over the next three years he graduated from a civilian aviation school, obtained a private pilot's license, withdrew from the University, worked for Boeing Aircraft Company, quit to join the Army Air Forces, returned briefly to Boeing and finally quit again to join the Navy.

Commissioned an ensign in 1943 following flight training, he served as a fighter and gunnery instructor and maintenance officer before spending six months overseas without seeing combat duty. While in the Navy he flew the F6F and F4U fighters, as well as SNJ trainers, and a variety of other aircraft.

Following the war he resumed his engineering studies under the G.I. bill and joined the naval air reserve unit at Sand Point Naval Air Station, flying fighter aircraft on weekends while attending the University of Washington. During this time he was a member of the navy acrobatic team flying FG-1D Corsairs at airshows around the Pacific Northwest. He graduated with a bachelor of science degree in aeronautical engineering in 1949 and earned his masters in aeronautical science the following year from the same university.

Crossfield joined the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA--the predecessor of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration or NASA) at its High Speed Flight Research Station, Edwards, Calif., as a research pilot in June 1950. During the next five years, he flew the X-1, X-4, X-5, XF-92A, F-51D, F-86F, F9F, B-47A, YF-84, F-84F, F-100A, YF-102, D-558-I and D-558-II. During that time he logged 100 rocket flights, making him the single most experienced rocket pilot.

He made aeronautical history on November 20, 1953, when he became the first person to fly at twice the speed of sound in the D-558-II Skyrocket. Taken aloft in the supersonic, swept-wing research aircraft beneath a Boeing P2B-1S (the Navy designation of the B-29) "mother ship", he dropped clear of the bomber at 32,000 feet and climbed to 72,000 feet before diving to 62,000 feet where he became the first pilot to exceed Mach 2 (more than 1,291 mph). His milestone flight was part of a carefully planned research program with the Skyrocket that featured incremental increases in speed while NACA instrumentation recorded the flight data at each increment.

Crossfield found more than his share of excitement during research flights. During the first air launch of the D-558-2 the airplane suffered engine trouble and the windshield iced over. Crossfield had to land without electrical power or radio communications.

"All I could do was put the sun in one place on that windshield and pray that I was right-side up," he said in a 1998 interview for the Dryden History Office. He managed to operate the radio with battery power and received landing assistance from a chase pilot.

Crossfield's first X-1 flight began with an unplanned spin, but he managed to right the airplane and complete the mission successfully. On another X-1 flight the windshield iced up during the landing approach.

"I was blind as a bat," said Crossfield. He asked his chase pilot for assistance and improvised a way to clear the ice away from the inside surface of the windshield. "I was wearing loafers and I got my shoe off and used one of my socks to wipe a hole in the ice so I could see." After landing he was unable to exit the cockpit because his foot was frozen to the rudder pedal.

Not all of Crossfield's flights ended successfully. On Aug. 17, 1953, he was forced to abort takeoff from Rogers Dry Lake at Edwards in the delta-winged XF-92A experimental jet. The airplane failed to stop on the runway and Crossfield managed to steer it onto a dirt road, finally coming to a halt well beyond the edge of the lakebed. The road was subsequently nicknamed "Crossfield Pike."

In another incident, on Sept. 8, 1954, he made a dead-stick landing in a North American F-100A during its first NACA research flight. After receiving a fire warning signal, Crossfield shut the jet's engine down and made a gliding approach and landing on the dry lakebed, similar to the type of landings he had performed numerous times in rocket planes. Without power, he coasted across the lakebed and up a concrete ramp to the NACA hangar. Unfortunately, he found the airplane's brakes now without pressure and could only watch in horror as the aircraft rolled into the hangar (barely missing other research airplanes) and penetrated the building's southwest wall. This spawned a joke that Chuck Yeager (first pilot to exceed the speed of sound) broke the sonic wall, but Crossfield broke the hangar wall.

On Sept. 1, 1959, NASA crew chief Bob Allen fastened Crossfield into the North American F-107A in preparation for a familiarization flight. He warned Crossfield not to taxi the aircraft too fast, as there was risk of a brake fire. Just before closing the cockpit, Allen told Crossfield, "This is the aircraft that separates the men from the boys." As Crossfield taxiied across the lakebed, the brakes caught fire, and the aircraft ground looped. It was damaged enough to be retired. Afterward, Allen said to Crossfield, "Now we know."

|

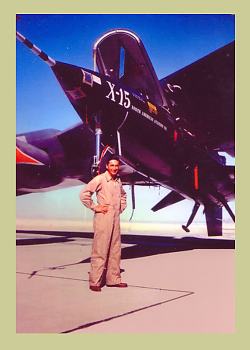

As a result of his extensive rocket plane experience, he was responsible for many of the operational and safety features incorporated into the X-15 and was intimately involved in the design of the vehicle. Crossfield piloted its first free flight in 1959 and subsequently qualified the first two X-15s for flight before North American turned them over to NASA and the U.S. Air Force. Altogether, he completed 16 captive carry (mated to the B-52 launch aircraft), one glide and 13 powered flights in the X-15, reaching a maximum speed of Mach 2.97 (1,960 miles per hour) and a maximum altitude of 88,116 feet.

Although Crossfield was not involved with the maximum speed and altitude X-15 flights, he found the early developmental tests not without risk.

During the fourth flight, on Nov. 5, 1959, an explosion and fire in the engine compartment necessitated an emergency landing on Rosamond Dry Lake near Edwards. During the steep approach Crossfield attempted to jettison the remaining propellants but was unable to complete the task due to the angle of attack. At touchdown the airplane was heavier than normal, resulting in a structural failure behind the cockpit that caused the bottom of the fuselage to drag on the ground.

Crossfield was also involved in tests of the XLR99 engine - at the time the most powerful and most complex man-rated rocket propulsion system. During a ground run on June 8, 1960, a malfunctioning relief valve and pressurizing gas regulator caused a catastrophic explosion. Although the X-15 was blown in half and engulfed in flames, Crossfield emerged unscathed. He later told a reporter the only casualty was the crease in his trousers. "The firemen got them wet when they sprayed the airplane with water," he explained. "Are you sure it was the firemen?" the reporter asked. Crossfield winced as he pictured the ensuing headline: SPACE SHIP EXPLODES; PILOT WETS PANTS.

In 1960, Crossfield published his autobiography (written with Clay Blair, Jr.), Always Another Dawn: The Story of a Rocket Test Pilot (New York: Arno Press, reprinted 1971) in which he covered his life through the completion of the early X-15 flights.

Following his work with the X-15 Crossfield remained with North American as chief pilot.

"I did the first flights on the T-39 for North American. At that time it was becoming abundantly obvious that aeronautics, as we had known it, were heading for the doldrums," he told the Dryden History Office. "There was just nothing coming along behind [the X-15]. All of the interest was in space, and that sort of thing."

Crossfield also served for five years as system director responsible for systems test, reliability engineering, and quality assurance for North American Aviation on the Hound Dog missile, Paraglider, Apollo Command and Service Module, and the Saturn V second stage. Then from 1966 to 1967 he served as technical director for research engineering and test at North American.

Crossfield served as an executive for Eastern Airlines from 1967 to 1973. Then from 1974 to 1975, he was senior vice president for Hawker Siddeley Aviation, setting up its U.S. subsidiary for design, support, and marketing of the HS-146 transport in North America. From 1977 until his retirement in 1993, he served as technical consultant to the House Committee on Science and Technology, advising committee members on matters relating to civil aviation. Upon his retirement in 1993, NASA Administrator Daniel S. Goldin awarded him the NASA Distinguished Public Service Medal for his contributions to aeronautics and aviation over a period spanning half a century.

His many other awards included the International Clifford B. Harmon Trophy for 1960 and the Collier Trophy for 1961 from the National Aeronautics Association, both presented by Pres. John F. Kennedy at the White House. He received an honorary doctor of science degree from the Florida Institute of Technology in 1982. Crossfield has also been inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame (1983), the International Space Hall of Fame (1988), and the Aerospace Walk of Honor (1990). In 2002-2003, Crossfield served as technical adviser for the Countdown to Kitty Hawk project, which successfully built and flew an exact reproduction of the 1903 Wright Flyer, as well as several of the Wright brothers' earlier gliders. That project culminated with the airplane's presence at the national centennial of flight celebration at Kitty Hawk in December 2003. Crossfield was a founding member and fellow in the Society of Experimental Test Pilots.

Crossfield held single- and multi-engine type ratings and an instrument rating for single-engine general aviation aircraft. In the late 1980s, after 20 years without much flying time, he purchased a 1961 Cessna 210A in which he eventually logged over 2,000 hours. By his 80th birthday in 2001, Crossfield was still flying 200 hours per year with a private pilot/instrument rating.

Throughout his life, Crossfield advocated aerospace education and was a strong supporter of the Civil Air Patrol (USAF auxiliary) and, in particular, CAP's aerospace education program. He created the A. Scott Crossfield Aerospace Education Teacher of the Year Award to recognize and reward teachers for outstanding accomplishments in aerospace education and for their dedication to the students they teach in kindergarten through 12th grade at public, private or parochial schools. Additionally, CAP senior members can qualify for the A. Scott Crossfield Aerospace Education Award. This recognition program is for CAP senior members who have earned the Master Rating in the Aerospace Education Officer Specialty Track.

Although revered for his flying exploits, Crossfield preferred to emphasize his role as a scientist.

"I am an aeronautical engineer, an aerodynamicist and a designer," he told Aviation Week & Space Technology magazine in a 1988 interview. "My flying was only primarily because I felt that it was essential to designing and building better airplanes for pilots to fly."