"I'll go alone."

HOWARD HUGHES AT THE CONTROLS OF THE XF-11 #1, HIS LUCKY FEDORA IN PLACE AS HE READIES THE AIRCRAFT FOR ITS ILL-FATED MAIDEN FLIGHT. THE RIGHT REAR SET OF COUNTER-ROTATING PROPELLERS SHOWN ON THE ENGINE IN THE FOREGROUND WILL BE THE ONES THAT FAIL IN FLIGHT AND BRING THE AIRCRAFT DOWN. |

Construction of the first XF-11 was completed in the spring of 1946 at the Hughes airfield in Culver City, California. Howard Hughes planned to perform the flight tests himself and scheduled the maiden flight for 15 April. Frank J. Prinz, a service engineer for Hamilton-Standard, accompanied Hughes in the cockpit for a high-speed taxi test to check the propeller operation. Distracted while concentrating on instrument readings, Hughes nearly ran the airplane into some trees at the end of the runway. Prinz flipped the prop-reverse switches and the XF-11 came to an abrupt halt. One of the tires blew, however, and the test flight was scrubbed.

Hughes accumulated several hours of taxi tests and rescheduled the maiden flight. During inspections the day after each taxi test technicians discovered that oil had to be added to the propellers, particularly the right-hand pair. Experience with the same type of propellers on other aircraft indicated that they could be run for an hour and a half before the oil quantity dropped to dangerous levels. The initial flight of the XF-11 was only scheduled to last 45 minutes.

On 7 July 1946 Hughes spent the morning conducting high-speed taxi tests during which he made several short hops into the air. Because Frank Prinz was not notified about the flight schedule, no one checked the oil levels in the propeller assemblies. Additionally Hughes, without consulting mechanic Gene Blandford, ordered 600 extra gallons of fuel to extend his flight time.

In the early afternoon several guests arrived to witness the flight. They included actress Jean Peters, war-hero/actor Audie Murphy, and Bill Cagney (actor James Cagney's brother). Hughes directed his test engineer Glenn Odekirk to take Murphy and Cagney up in the A-20 chase plane during the test flight.

At last, Hughes was seated in the cockpit with the engines running. He taxied to the end of the runway for final checks. At one point, Blandford climbed up into the cockpit as asked Hughes if he wanted him to go along. "Well," replied Hughes, "I'll go alone." Blandford climbed down and, 10 minutes later, Hughes was ready for takeoff.

Following an uneventful takeoff, Hughes began to put the XF-11 through its paces while the crew of the A-20 observed from above and behind. He circled Culver City at an altitude between 5,000 and 10,000 feet for about 40 minutes. While cycling the landing gear, Hughes noticed a warning light on his control panel.

THIS PHOTO, TAKEN THE NEXT DAY FROM THE ALLEY BEHIND 808 N.WHITTIER SHOWS WHAT REMAINS OF THE HOME WITH THE XF-11's WRECKAGE PILED IN THE BACKYARD. ARROWS INDICATE SOME OF THE IDENTIFIABLE WRECKAGE (1) ONE OF THE MAIN LANDING GEAR MINUS TIRE AND WHEEL (2) ONE OF THE TWIN FUSELAGE BOOMS (3) THE RIGHT VERTICAL STABILIZER WITH THE CENTRALIZED HORIZONTAL STABILIZER AND ELEVATOR STILL ATTACHED. THE IMPACT MARKS IN THE DIRT FROM THE AIRCRAFT'S PASSING CAN ALSO BE SEEN IN THE LEFT FOREGROUND. |

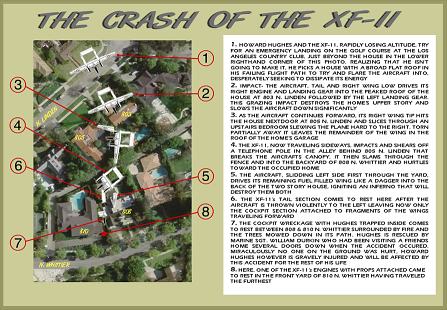

While working the gear problem Hughes found himself several miles east of the airfield, heading north over Beverly Hills at about 5,000 feet. Suddenly, he felt enormous drag on the right wing and the XF-11 turned eastward. Hughes wrestled it into a 180-degree turn, losing altitude at an alarming rate.

Misinterpreting these maneuvers as preparation for a return to Culver City, Odekirk and Blandford turned the A-20 around to land ahead of the XF-11.

BEVERLY HILLS FIREMEN EXTINGUISH THE WRECKAGE OF BOTH 808 N.WHITTIER DRIVE AND THE XF-11. THE COMPLETE TAIL SECTION OF THE AIRCRAFT CAN BE SEEN LYING FRONT SIDE DOWN WITH ITS SERIAL NUMBER CLEARLY VISIBLE. |

Meanwhile, Hughes was desperately trying to figure out what was wrong. He loosened his seatbelt and moved about the cockpit, trying to get a better look at his stricken plane through the canopy bubble. He didn't realize that one of the counter-rotating propellers on the right-hand engine had suddenly reversed pitch due to the undetected oil leak.

He tried increasing manifold pressure and increasing the propeller speed. He cycled the throttle for the right-hand engine without effect. By now he was down to 2,500 feet, too low to bail out.

Holding full left rudder and aileron to maintain control raised the spoilers on the left wing causing further loss of lift. He lowered the landing gear and aimed for the golf course at the Los Angeles Country Club, but it was too late.

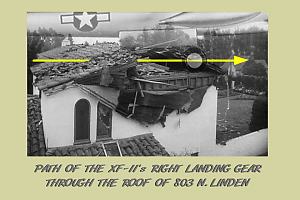

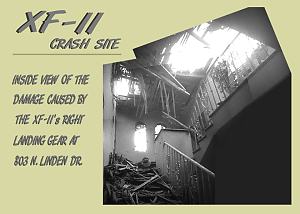

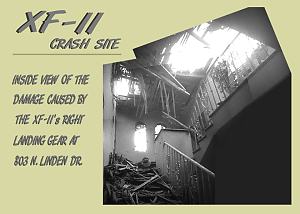

Hughes ran out of altitude only 300 feet short of his goal. As he rapidly approached the Spanish tile roof of 803 North linden drive, he pulled back on the yoke. The landing gear and right engine tore through the roof and second-story wall. The right wingtip struck the neighboring house at 805 North Linden, but momentum carried the XF-11 across an alley and through the poplar trees behind 808 Whittier Drive. The airplane slewed violently to the right, sheared off a power pole, and skidded across the backyard at 808 Whittier. Parts of the airplane were scattered all the way to the street and the fuel tanks exploded setting the house ablaze. The piecemeal breakage of the airframe as it crashed through yielding structures bled off much of the plane's kinetic energy, saving Hughes' life.

|

Pulling himself from the crew cabin, Hughes staggered out of the cockpit onto what was left of the wing and then tumbled to the ground. A bystander, Marine Sgt. William Lloyd Durkin, pulled him to safety.

HERE, ONE OF THE XF-11'S ENGINES IS SHOWN LYING IN THE FRONT YARD OF 810 N.WHITTIER DRIVE WITH THE BURNED REMAINS OF 808 N.WHITTIER AND THE XF-11 IN THE BACKGROUND. THE BACK END OF THE ENGINE FACES THE CAMERA AND SEVERAL OF ITS EIGHT COUNTER-ROTATING PROPELLER BLADES CAN BE SEEN BENT AROUND AND AWAY FROM IT. |

Hughes suffered a broken collarbone, six cracked ribs, third-degree burns on his hands, internal bleeding, and contusions to his lungs. He was rushed to the Beverly Hills Emergency Hospital then transferred to Good Samaritan Hospital in Los Angeles. The resulting 35-day medical treatment left him addicted to painkillers and steroids.

The accident investigation board determined that the primary cause was a propeller malfunction. They noted, however, that if he had followed the original flight plan, he would have been on the ground before the failure occurred. He also was criticized for not using the assigned radio frequency, retracting the landing gear (something not normally done on a maiden flight), not knowing the correct emergency procedures, failing to correctly identify the problem, and not attempting emergency landing when sufficient altitude was still available.

From his hospital bed, Hughes applied the harsh lessons learned from his accident. He ordered that the second XF-11 be equipped with single four-bladed propellers instead of counter-rotating sets. This was accomplished and on 5 April 1947, he climbed into the cockpit of the remaining prototype.

The test flight and most subsequent ones were uneventful, although Hughes tempted fate again when he pushed a full-stall test to the point where it resulted in a 10,000-foot split-S maneuver. The airplane was eventually tested at Muroc (now Edwards AFB), California, and later Eglin Field, Florida. Production, however, was ultimately cancelled and the XF-11 was scrapped.

Once, when an FAA test pilot asked Hughes why he didn't simply hire someone else to do his test flying, Hughes replied, "Why should I pay somebody else to have all the fun?"

© Copyright 2004-, The X-Hunters. All rights reserved. Copyright Policy Privacy Policy Page last modified 05/01/2023